Robot Roller-Derby Disco Dodgeball has been officially released for one year, so it’s probably a good time to share some data, lessons learned and talk a bit about what’s next.

The tl;dr highlights:

- Sales and user reviews were great - $700K revenue and over 90% positive user reviews.

- Primary drivers of sales were YouTube, streamers, and Steam Discovery.

- Despite over 140K owners, has been hard to grow a large online community. But it has been maintained at a moderate level via game updates, discounts, & continued YouTube exposure.

- Will soon be permanently dropping the base price as an experiment.

- Still planning updates, but beginning shift to new project which you can follow via Twitter or mailing list.

Brief History of Disco Dodgeball

Robot Roller-Derby Disco Dodgeball is a first-person sports-based arena shooter where you drive wheeled robots around a dance club / skate park and score trick shots off each other with bouncy dodgeball projectiles.

I’ve been working on it for 2.5 years, primarily on a solo basis although I did hire some very talented people for contract work that made it much more professional than I could have on my own.

It’s my first PC and Unity project, having spent the 3 years prior building native iOS games.

Development began in July 2013. I built a functional prototype in a few weeks and felt it was immediately fun and satisfying just to launch off ramps and throw a bouncy ball around. Then I added basic online multiplayer, posted it to reddit, saw it got some good traction, and decided to pursue the idea fully.

I soon put it up for sale via Humble Widget so that I could capture the initial attention. It was Greenlit in November 2013, released in Early Access in March 2014, officially launched in February 2015 on Steam and Humble Store and has been receiving steady post-launch updates ever since.

Reception

Player response was very positive - through most of its time in Early Access the hundreds of Steam reviews were 100% positive and when it launched it was the top-ranked multiplayer game (and 4th overall) in Steam when sorting by rating. I think this can be attributed to the fact it was fun and playable early on, plus frankly there wasn’t a ton of public hype at that stage so the risk of disappointment was low. I also spent a lot of time in the game’s forums responding to player questions and bug reports, and made sure not to overpromise on timelines or features. So Early Access was a pretty smooth ride from that perspective.

The player rating has since drifted down to 93% positive (1633 positive and 114 negative). It seems that whenever the game goes on discount it attracts a new handful of negative reviews, plus I think some new players are expecting a higher concurrent player base which is absolutely fair. The roller-skate movement can also turn off new players expecting a more traditional tight FPS control and rapid-fire-clicking instead of one more based on flow & opportunism. The positive reviews tend to mention things like the soundtrack, gameplay variety, high skill ceiling, disco lights, and generally describe it as fast-paced, easy to pick up, and fun.

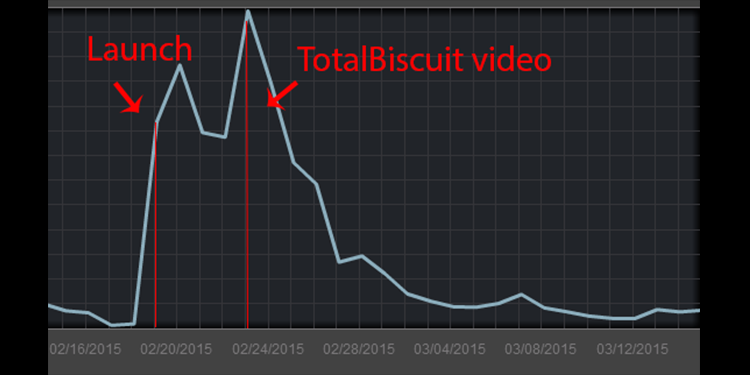

On YouTube, it got tons of attention - the top 40 videos have around 11 million views between them and many of the top YouTube and streaming channels played it at one point or another. TotalBiscuit gave it a very favorable response in a ‘WTF’ video released during launch week, which had a dramatic impact (perhaps doubling launch week sales). During Early Access, it did get panned by Jim Sterling which was a big bummer for me because I was trying really hard to do Early Access right - selling a game that had strong core gameplay with meaningful updates on a regular basis, and although it lacked polish and advanced features I felt it was worth the price I was charging and players liked being involved in the development. Still, it highlighted the need for a better new user experience so players could get off on the right foot particularly with the unorthodox controls.

In terms of traditional press, things were pretty muted. To date it still doesn’t have enough metacritic-qualifying reviews to receive an official score - it has only 3 reviews, averaging 70 points. It did get some very positive reviews scores (95/100 from DestroyTheCyborg, 8/10 From OperationSports, 9/10 from IndieHaven, 4/5 from HardcoreGamer) as well as non-reviews from larger sites such as PC Gamer, and Wired ("Robot Roller-Derby Disco Dodgeball is as amazing as you'd expect"). Giant Bomb did a few videos of it right before it launched, which had a significant impact on downloads and gave good momentum going into launch, but there unfortunately wasn’t a follow-up article or video post-launch from them.

Revenue

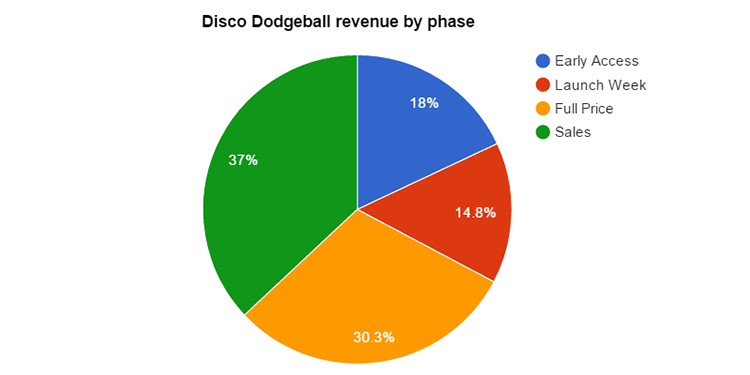

Overall the game turned out to be a very good financial success, bringing in gross revenue just under $700,000 (combining Steam, Humble Store, and Humble Bundle revenue) across 140,000 copies (counting a 4-pack as 4 copies). As you can see from the chart below, the greatest share of revenue came from ‘long tail’ sales but somewhat surprisingly full price units accounted for nearly the same share of revenue. (In the chart, 'Full Price' and 'Sales' only count units sold after launch week, so there's no overlap with other pieces of the pie.) The game was in Early Access for 11 months and has been officially launched for 12 months, so the daily rate post-launch was much higher than during Early Access (82% vs 18%). Launch week was solid (the first day was nail-biting but the week finished strong) and wound up accounting for ~15% of total revnue.

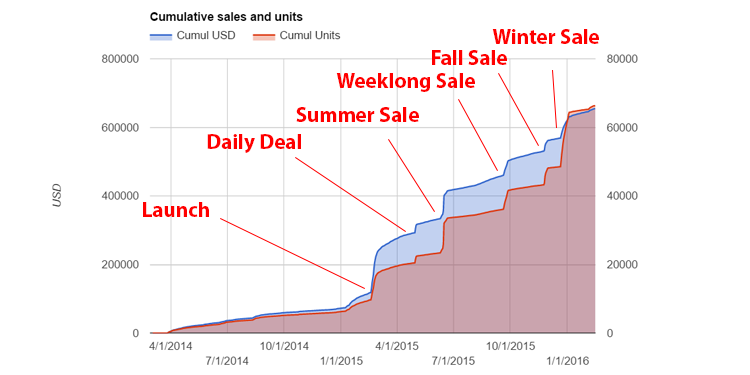

Here’s a cumulative graph of revenue (top blue line) and units (bottom red line) over time. You can see again here that sale events were significant but the default growth rate has a good slope indicating a meaningful baseline of daily revenue.

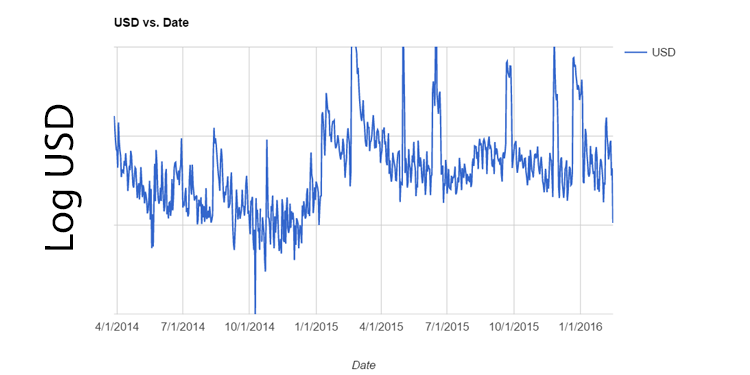

Below is a graph of sales rate per day (logarithmic scale, with peaks cut off). This illustrates that big sales didn’t dramatically affect the daily baseline sales rate much. I wasn’t sure which way this would go - either big sales would cannibalize full price units, or they would generate a ton of new interest due to it being a multiplayer game and actually increase normal unit rates. But either these two effects counteracted each other, or they only have a noticeable effect when the units involved are much larger. Given the fact that daily full-price sales barely changed even while the game was available for extremely cheap in a Humble Weekly Bundle, my hunch is for the most part full price buyers and discount buyers are isolated markets and that the cannibalization of full price units via sales is not as strong a phenomenon as many developers fear.

The big difference you see in the chart below starting in January 2015 was when it first got Giant Bomb press coverage and worked its way into the 'Overwhelmingly Positive' ratings group on Steam (>= 500 reviews, >= 95% positive), the combination of which dramatically increased sales rate and this carried through launch a month later after which it stayed pretty constant.

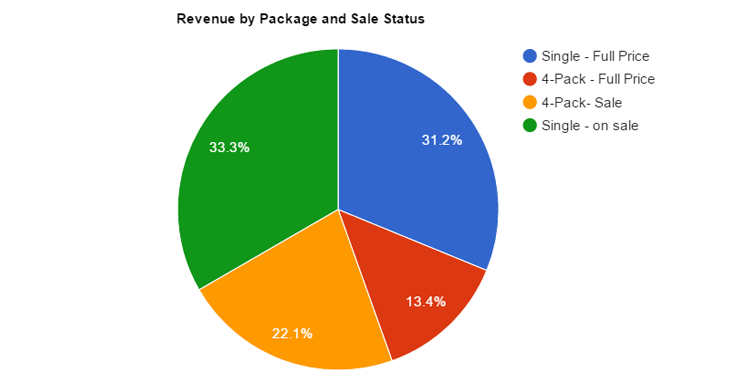

One other interesting effect is 4-packs accounted for ~ 35% of total revenue. During a sale, 4-packs sold particularly well. It’s impossible to know for sure if total revenue would have been higher without the 4-pack option available, but my hunch is that the high price of the 4-pack provided an anchor that made sale units more attractive and probably encouraged many players to upgrade to a 4-pack instead of a single copy (benefitting both revenue and player counts).

About 25% of people who ever had it on their wishlist have since bought it or received it as a gift or trade. And about 15% of current owners had it on their wishlist at some point.

Before moving on, it’s also important to provide context to that total revenue number: First, it’s cut in half by platform fees, taxes, and refunds. Then it has to account for development expenses: the game directly cost about $40,000 to make (art assets, sound effects, soundtrack licensing, desk space, software licenses, PR assistance, conferences, expos) plus 2.5 years full-time work on my part which tacks on an arbitrary dollar amount somewhere between ‘raw living expenses’ and ‘opportunity cost of working in a non-games tech job’. Additionally it has to subsidize the past several years of independent development that were not nearly as profitable, and perhaps the next few as well.

Again this is not meant as a complaint, it’s just to provide some perspective on game dev as a business. It’s a result I’m certainly very happy about, mostly because it means if I am reasonable about expenses I get to keep making games for a while.

Strengths

Here are some factors that I think contributed to the project’s overall success:

- Familiar, but different. The game benefits from being in a popular and marketable genre while being mechancially and aesthetically distinct enough to occupy its own niche and avoid direct competition / comparisons with billion-dollar franchises. The concept of a dodgeball FPS is something people can immediately latch onto and see the appeal. There are so many games being released these days that you have to do everything you can to avoid being an interchangeable commodity, and Disco Dodgeball’s combination of one-hit-kill projectiles, trick shots and sport objectives scratches a very particular itch that existing shooters don’t.

- Straightforward design. This was actually a very easy game to design - once the basic movement and throwing system was developed every trick shot, game mode and powerup felt like obvious extensions that enhanced the game without creating excessive complexity. Even from the days it was a week-old prototype it was fun just to throw a ball around and launch off ramps, and all it needed were some objectives and modifiers to keep things interesting. I’ve built games in the past that took excruciating months to be fun, so it was a nice treat to feel like the whole game was laid out from the start. I think the fact that the ‘good stuff’ was so close to the surface is something that players could detect as well.

- Unique theme. Being a silly dodgeball game meant I wasn’t tied to convention and had a lot of latitude for unusual thematic elements like disco lights, mustachio’d robots with googly eyes, jetpacks and sunglasses. These differentiators helped it stand out from other games in the genre yet somehow worked together as a cohesive whole. Even better all these elements fed back into the gameplay by reinforcing that it’s a fun / chaotic party game.

- Reasonable scope. It’s a project that was for the most part a good fit for my limitations (budget, personnel, experience). The mix-and-match style of modes, levels, and modifiers combined with the unpredictability of human competition created a huge amount of replayability from a relatively small amount of hand-crafted content. I also deliberately chose the simpler path of non-human, non-animated character models because anything I could reasonably create or pay for would still not compare favorably to AAA games. By taking this orthoganal approach and not trying to beat Call Of Duty at its own game I think I was able to punch above my weight class in terms of marketability.

- Attractive to YouTubers and Streamers. The game is visually appealing, has an attention-grabbing premise, is chaotic fun and easy to get into as a player and viewer, so it wound up being a popular game for video content. Being a multiplayer game fed into this as well because channels tended to do collaboration videos. Some of the videos are still getting millions of additional views over time which is boosting up the long sales tail. In addition the millions of views gave it high awareness that was a big benefit during launch, which in turn snowballed into better Steam visibility.

When I first started developing the game I contacted a lot of small and medium channels and got good pickup there, and then larger channels noticed it from there or had their viewers recommend it to them. So there's a big network effect within YouTube that can generate a lot of additional coverage.

- Timely video by Total Biscuit. As far as I can tell it doubled my launch week, and that in turn very likely helped establish a higher baseline from which the game would benefit over the long term. I consider this a very lucky break, as it only came to his attention because his wife picked it for a Snark Tank episode where they poke fun at game trailers. Just like how poker is a game of leveraging odds in your favor, Disco Dodgeball’s lenghy name and ridiculous trailer helped create this opportunity. But considering the huge impact it had I can’t help but feel extremely lucky here.

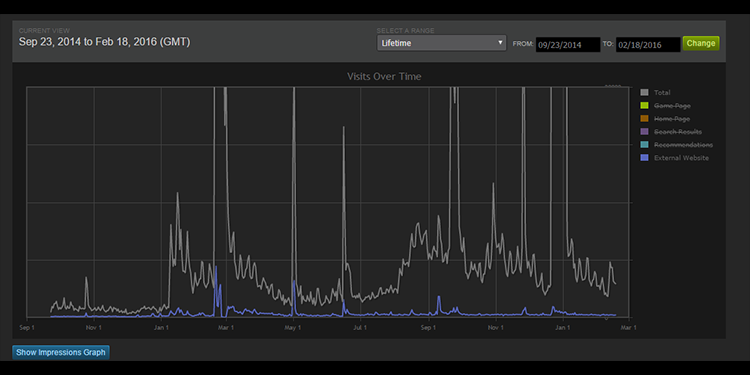

- Steam Discovery Traffic. Good reviews and decent sales probably fed into Steam’s discovery algorithm, leading to get a very nice boost there. Since the Discovery Update, Disco Dodgeball has received over 1.5 million game page visits via the Discovery Queue and another .5 million from main cluster recommendations. In the chart below, the blue line is traffic from an external website and everything else is basically driven by the Discovery Queue and Recommendations. The big peaks in discovery traffic correspond to major sale events regardless of whether it was featured.

I don’t know the inner workings of the algorithm but it seems likely to be some combination of player ratings, number of owners, number of wishlists, curator lists, search traffic and external traffic. Discovery traffic very closely mirrored sales numbers, which leads me to believe a lot of my revenue came from these Steam discovery features - the game very well may have been invisible and sold dramatically fewer copies without it.

- Sale Features. This was another lucky break that I had very little direct control over. The game received a flash sale during the 2015 Summer sale, resulting in its best single day of revenue. It also got a non-flash feature during the smaller Fall sale. My best guess is that Valve’s algorithm surfaced Disco Dodgeball as a feature candidate for the same reason it was getting good discovery / recommendation traffic. While the game did sell surprisingly well during a self-run weekly sale (thanks again due to recommendation traffic) these main feature spots during huge front-page traffic periods are undeniably valuable.

- Good soundtrack. As a game taking place in a dance club, it was imperative to have the right music. I think this is something that resonated with players and seemed to be a common reason (based on random web mentions and Steam reviews) why they would tell each other about the game.

- Open Development. From the very early prototype stage I had the game available to the public and was gathing tons of feedback and feature requests from players. Not only did this provide me with tons of great ideas, I think players really appreciated being part of the process and that helped create a number of dedicated players that stuck around far longer than they would have otherwise. It certainly allowed me to bootstrap a playerbase in a way that a closed platform like iOS would have made imposible.

- Positive Community. The online community wound up being generally very positive to each other. Perhaps a function of the competition being nonviolent and rather casual, or just that the playerbase was smaller and tight-knit. I built a simple 'Kudos' system that let a KO'd player easily congratulate the person who hit them, and I think this set the tone and expectations early on for new players.

Weaknesses

Of course, I know there’s also missed opportunities and suboptimal decisions that decreased potential sales. Note that several of these items are also listed as strenghts - there were a lot of double-edged aspects to deal with.

- Open Development. Since anyone could get the game at anytime, there was no massive build-up of hype and demand which sometimes can result in a much larger launch peak at launch. However this approach is a pretty risky ‘all-or-nothing’ situation and in hindsight I doubt I could have really generated the advance interest and demand necessary for that thunderclap effect.

- YouTube coverage too spread out. Due to the fact the game was available to play for over a year before official Steam launch, YouTube and Twitch coverage occurred in smaller chunks over a long period of time and actually seemed to die off a bit before the game even launched. For instance, NerdCubed covered it during greenlight, Markiplier covered it after greenlight but before it was available on Steam, and many other huge channels covered it while it was still in Early Access. If chance or better coordination on my part had made that more concentrated exposure right before and during launch it could have had a much bigger impact.

- Lack of Prestige. I don’t have a very high profile as a developer, or personal connections with many writers or other highly visible developers, nor was the game already a cultural phenomenon, so getting traditional press was definitely a challenge. I do feel the game is remarkable for being mechanically innovative in many ways, but I was never able to convince the press at large that it warranted that kind of thorough analysis. I did wind up getting some big-name coverage but it was again pretty spread out or was more of a 'first impressions' style so it never really changed the sales momentum. Many sites that gave it a mention never did a full review. It very much felt like I was developing the game in a press vacuum and that was pretty disheartening.

Looking back, I think YouTube had a much greater impact on overall awareness and sales, so I probably spent a bit too much mental energy stressing about this aspect during its development.

- Lack of engine experience. This was my first Unity project, so it look me a lot longer to get anywhere close to the visual results I wanted. I spent tons of time redoing textures and lighting and still feel it’s sub-par. I hired artists for necessary components like icons and character models but just wasn’t able to commit the budget for the full art design overhaul that it could probably use. At some point you hit diminishing returns on those kinds of investments - and at this point prettier visuals wouldn’t really make the game more fun or fix the playerbase - but I’m also sure the programmer-art feel turned away a number of users looking at store page screenshots.

- Lack of competitive features. There’s several competitive-based features I never implemented that perhaps could have dramatically increased player retention, such as ranked matches. In part I was waiting to see if the game ever reached the critical mass that would make these features useful without fragmenting the playerbase, but I was also afraid my limited time and lack of expertise would lead to easy abuse by hackers, thus negating my efforts and eating up future development time in a never-ending battle to combat cheating. In addition, those competitive modes would have required much tighter networking tolerances than I was capable of delivering. So I wound up never adding them, and this probably led to a higher rate of player drop-off without these ladders to climb.

- Multiplayer. A lot of people are probably hesitant to buy into a indie multiplayer game for fear of it dying out before they get their money’s worth. This of course can easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy. While I sold enough copies and designed the game in such a way to counteract this to some extent (more on this below), I’m sure it also means some people gave it a pass that might have otherwise bought it.

- Lack of localization. I never got a chance to localize the game, and this certainly cuts a percentage off of total sales. I had a few YouTube videos from large (million+ subscriber) non-english channels and I noticed the sales impact from those was very muted and perhaps this was a result of non-localization. (Or maybe it was the fact they linked to an unauthorized G2A affiliate link instead of Steam or Humble...grr!)

- Spread a bit thin on features. I generally spent my time adding more features rather than polishing existing ones, which gives a lot of things in the game a half-finished feel. For instance the ‘match over’ screen, which should be a pyrotechnic highlight reel of accomplishments, item drops and level-ups is just a bare-bones menu with a sprinkling of stats. It’s often little things like this that create compelling gameplay loops and keep players coming back for more, and I could have probably spent an additional year just polishing up existing features and interfaces.

- Pricing(?) I launched with a price of $15, which is a reasonable price for a small-studio game in today’s market but very aggressive for a primarily multiplayer game. There are several highly polished arena shooters for around that price or even free. It’s possible that a $10 price point or lower would have dramatically increased its uptake, especially if that lower price signal helped it overcome trepidation about the activity level of its community.

On the other hand, the higher price point meant that when it was one sale, it tended to do very well. Ultimately the flow of new players was good from a revenue perspective but not enough to counteract attrition and grow the active playerbase.

- Inability to keep spotlight. I spent the past year making significant overhauls to the game, adding things like Steam Workshop, item drops, trading, new game modes, new levels, and a custom game mode editor. However none of these updates converted to a dramatic impact on active playerbase, sales, or awareness. A handful of dedicated players would be excited about it, but game updates definitely weren’t ‘press-worthy’ like they are for more popular games. From my end, I certainly could have done more outreach here, put together more polished update videos, etc. - but given the limitations of being a solo developer that would have meant slowing down development.

Similarly it was rare for YouTubers to make multiple videos of the game, so there’s something about the design of the game compared to other multiplayer games that lets people ‘get their fill’ upfront without much desire to return. Or, this is an effect of the game not having a huge wave of buzz that incentivizes YouTube channels to cover it en masse.

Playerbase Challenges

Going into this project I was well aware of a phenomenon sometimes called the ‘Indie Multiplayer Curse’. That’s where projects from small studios never get a critical mass of online players, then sales suffer as players are afraid of buying into a dead game and/or leave bad reviews, which then further drops player counts. It’s a nasty death spiral and even high-profile AAA games fall victim to this on a regular basis. You can identify it by the pattern that on launch week the concurrent player count drops to low single digits and never recovers.

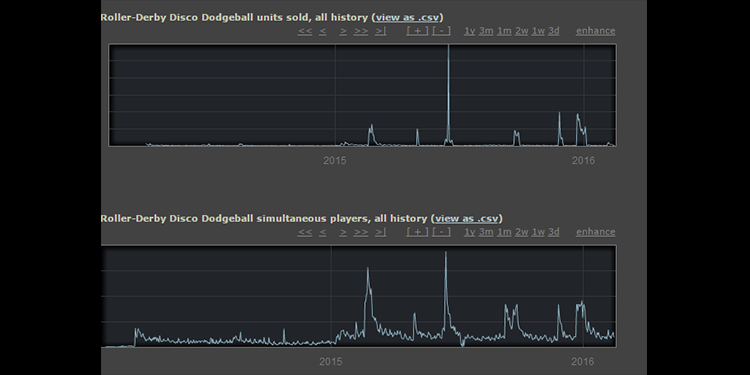

I’m happy to say I avoided this fate, but not by a very wide margin. The concurrent player count pretty much peaks at 30-50 players a night. At the best peak times (at launch, or during a big sale) it would get in the low hundreds, but very soon after would fall back to the baseline. This level of activity is enough to find a few open rooms and play some matches, but only if you log on at peak times on certain servers or organize scheduled play sessions. It’s certainly better than zero and is actually quite a feat for a year-old game, but still far short of the hundreds or even thousands that would be ideal.

My approach to keeping the playerbase active included these steps:

- Photon Cloud servers available so that any player can create a room from scratch without any server setup knowledge

- Matches are jump-in, jump-out so there’s no queue or penalty for leaving

- XP gain and item drops to reward playtime & give players an incentive / opportunity to show off

- Bot AI players to fill up rooms, so there’s no need to sit idle in an empty room waiting for players

- Robust singleplayer options as a fallback option to reduce hesitancy to buy

- A lot of content variety

- Aggresive sales schedule & eventual bundle

- Frequent game updates

I think these steps are what helped it stay alive as long as it has and get off the ground in the first place. But to really make it take off I would need much greater retention (perhaps via more competitive aspects) as well as a greater rate of new players in.

As you can see from this chart below, I’d get a nice influx of new players during a sale but they’d drop off soon after. Also, lots of people who picked it up during a sale wouldn't play it immediately - I might see a 20x increase in units sold during sale but only a 5x growth in active players for that period.

Total units sold was perhaps large enough to create a critical mass, but they were spread out over a long period of time and I didn’t have an effective communicaiton method for getting them all back in the game during updates.

A lot of multiplayer games have progresion systems built in to kite player attention over longer timespans, but the design of Disco Dodgeball doesn't lend itself well to that. There's only one weapon - the dodgeball - and I didn't want to confer advantages like powerups or perks to expeienced players as this would further fragment the playerbase. I do have cosmetic unlocks but that didn't provide enough incentive to keep playing & levelling.

I could have also spent more time running tournaments or having special time-limited events, which is what a lot of games do to keep players active. Unfortunately that’s also one of the sacrifices I had to make as a solo developer since I couldn’t do that and also keep developing new features.

Building a multiplayer game means you are playing a very difficult numbers game. You need a huge stream of new players in, you need to keep them around for a long time, and you need to be able to bring them back on a regular basis. If your game has queues or skill tiers you need to multiply those already high number requirements. You’re also in an environment where eSports giants Dota, LoL, and CS:GO consume a ridiculous number of competitive player hours. On top of that you’re dealing with the seesaw of concentrating players on a few servers vs. spreading them out on servers that will give them better connections. It’s difficult even just to scrape by as Disco Dodgeball does, and it's a very rare (or free) game that can maintain decent populations.

What’s Next

Ultimately I’m very happy with how Disco Dodgeball turned out as a game, and feel very fortunate that it was a commercial success. I really enjoyed jumping in matches and playing the game with people - it still feels pretty surreal to have something that at one point existed only in your head become a shared reality like that. My one big disappointment is that I haven’t been able to grow the playerbase to where I think it ought to be, and so in that sense still feels like a lot of wasted potential.

Given that the game is a year old, it’s time to try permanently reducing the base price of the game and see if that increases the daily influx of players enough to change the concurrent playercount trajectory. I’ll cross my fingers that it breathes new life into the community and I have a hunch it could actually increase total revenue - I’ll make sure to post an update once I get some good data.

[Update May 2016: I dropped the price in half to $8 soon after this post and it roughly doubled unit sales, so revenue basically stayed constant with perhaps a slight increase. Concurrent user counts have barely changed though, so perhaps players think the game is half as valuable and invest half the time in it? Hard to tell.]

I’m planning at least one more major update to Disco Dodgeball to add local multiplayer, and will probably add new modes & levels to it over time as long as there’s still interest in the game.

But I’ve also got a serious itch to start working on a new project, and in my weekends have been prototyping a new FPS (which will be primarily if not exclusively singleplayer). I’m only a few dozen hours in, but it already feels compelling like how Disco Dodgeball was in its early days, so I’ll count that as a very good sign.

Thanks for reading and I hope you found this informative or helpful in some way. Of course another huge thanks for everyone that played or supported Disco Dodgeball, you're the reason I get to keep making games. And if you’d like to receive updates on these future games you can follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list. Cheers!

Erik